Deliberate fires in the valley, spring 1939

The region:

The level of ecosystem destruction, generated by intentional bushfires of the 1920s-1940s, is comparable to the 2019-2021 bushfires in the world: Australia, Brazil, Russia (Siberia), US (California), etc.

In the prehispanic colonisation period the local native peoples provoked burns in the steppe and forests, as attested by several writers: Arnold Heim (Leones valley), George Musters (1870), Francisco Moreno, Andreas Madsen (see Publications). Fires were deliberate, there are no naturally occurring fires as there are no thunderstorms in the region (climate particularity). The pattern of these fires was different from the XX century’s fires: these were small and very localised, people moved further and nature had the possibility to recover.

““Pristine” areas are artifacts by humans.

In Chile they exterminated megafauna and changed the landscape.”

“ The World Without Us”, Alan Weisman.

The region lost almost all its ancient forest cover mainly through the total clearing fires following the colonisation of the first half of the XX century, from approximately the 1900s to the 1950s, depending on the progress of the colonisation to South. Clearing the land from forest was a condition for receiving a land title for it by the new “occupants” of the land. The main clearing method was burning. It is well attested in publications on the history of the region, for example in this one, describing the process of distribution of land to colons via the “occupation of land by fire”: Colonizacion Rio Baker.pdf , or in Memoria Chilena and many other, see Publications. Companies had a legal obligation to “colonise” (“obligación de colonizar”) using the same methods.

This method of “land management” is still widely used in South America

The history of this ecological disaster provoked by the fires was particularly silenced: according to recent publications about 3 millions hectares of forest were burned in the Aysén region in that period,

accounting for at least 50% loss of the total vegetation cover of the region, and massive forest ecosystem losses in the 1930s-1940s, nearing or reaching ecosystems collapse:

Patagonia on fire.pdf A good summary of the tragedy of the forest in the region:

Geographic silences.pdf La tragedia del bosque chileno.pdf

The trees you see on hills in the region are results of these fires.

The open space you see in the region and its “tremendous”

landscape used to be an ancient forest in the beginning of the XX century.

The amount of forest burned corresponds to the surface of forest

fires in Siberia in 2019, which was declared a world catastrophe.

The project’s area:

The original pre-colonial ecosystem of the valley was ancient Nothofagus

(southern beeches) forest. No original peoples were living in this part of the region, some moved in from other regions following colonisation. There are no thunderstorms in this area. The absence of natural or man-made fire occurrences shaped a forest ecosystem where fire was not part of the normal ecosystem cycle. Fires reinforced local climate change and vice versa. Total and fast clearing burning was therefore a annihilating disaster for local nature.

The land was distributed and its original land titles assigned to the properties, forming the actual project, in the late 1930s. These properties were cleared by fire in spring of 1939, all 1800 hectares of the project’s area were burned.

Subsequent overgrazing and soil changes did not allow the forest to regrow.

Little ecological memory was left after the fire history of the region. It cannot be used to restore forest ecosystem resilience. Usually after forest fires a strong ecological momentum remains in vegetation, some in wildlife, and ecological amnesia in insects, but in this case time was lost for all momenta.

No indigenous culture left, no traditional ecological knowledge or hight values assigned to the living nature and wildlife can help the assessment or revitalisation of the pre-fire forest.

There is still some possibility to transform the effects of large disturbance by fire into some minor positive effects for the ecosystem: deadwood, insects, food for birds and bats, etc.

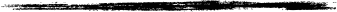

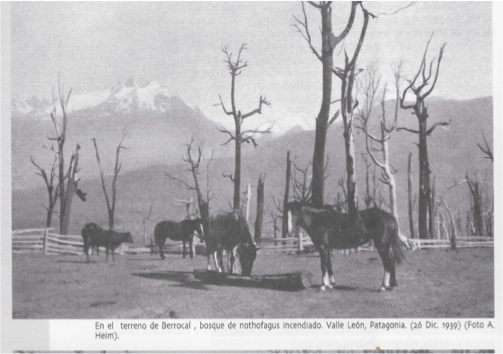

The area of the Project in 1939, straight after the burning, photos from A. Heim’s book.

High areas of the project now, where the burned trees have not been used for firewood or otherwise cleared because of difficult access:

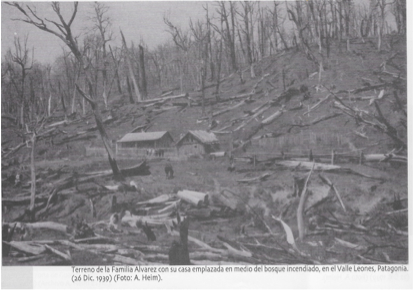

Ancient forest forest burned in 1939 in the valley

Large burned in 1939 lengua tree

Like a warm tear of dew -

A drop dripped in the eye.

There, in the heavenly height,

Someone is crying for me.

Marina Tsvetaeva,1920

Словно теплая слеза -

Капля капнула в глаза.

Там, в небесной вышине,

Кто-то плачет обо мне.

Burned lenga tree (Nothofagus pumilio)

ANÁLISIS HISTÓRICO-JURÍDICO DE LA REGULACIÓN DEL BOSQUE NATIVO EN CHILE: ORIENTACIONES Y FINALIDADES EN LA LEY 20.283, FELIPE ANTONIO MORENO DEL VALLE , Santiago, Chile 2015:

p. 35

La campaña de colonización de estas inmensas comarcas, implicó la inmigración de miles de familias europeas quienes se asentaron en estos territorios. Tanto por parte del gobierno de Chile, como por los mismos colonos, con el fin de instalarse y dar paso a la agricultura y ganadería, se dio comienzo a un periodo de devastación del bosque sin precedentes hasta ese entonces en nuestro país, ocupando el fuego como principal aliado para despejar los terrenos cubiertos por árboles. Vicente Pérez Rosales, designado por el gobierno de Manuel Montt como agente promotor de la colonización, describe en estos términos la simplicidad con que se abrían mediante fuego y hacha el espacio para los nuevos pobladores: ―En mi tránsito, ofrecí a Pichi-Juan treinta pagas, que eran entonces treinta pesos fuertes para que incendiase los bosques que median entre Chanchán y la cordillera(...) Hacía ya tres meses que el disco de ese astro, siempre puro allí cuando se deja ver, aparecía empañado. Pichi-Juan había dado, desde entonces, principio a la tarea de incendiar las selvas que ocupan gran parte del valle central al S.E. de Osorno. El fuego, que prendió en varios puntos del bosque al mismo tiempo tomó cuerpo con tan inesperada rapidez, que el pobre indio, sitiado por las llamas, solo debió su salvación al asilo que encontró en un carcomido coigüe, en cuyas raíces húmedas y deshechas pudo cavar una peligrosa fosa. Esa espantable hoguera, cuyos fuegos no pudieron contener ni la verdura de los árboles, ni sus siempre bien sombrías y empapadas bases, ni las lluvias torrentosas y casi diarias que caían sobre ella, había prolongado durante tres meses su devastadora tarea (PÉREZ ROSALES. Vicente. 1893. Recuerdos del pasado. Santiago. Editorial Andrés Bello. 112p). El uso del fuego en las actuales regiones de la Araucanía, Los Ríos y Los Lagos, se utilizó en forma indiscriminada para habilitar zonas de pastoreo y de cultivo

de cereales. ―El Estado impulsó durante más de cien años un proceso de colonización en tierras forestales, sin planes ni criterios de uso sustentable. Se entregaron tierras en zonas muy apartadas a campesinos e inmigrantes europeos pobres, que no contaban con capital ni conocimiento para hacer un uso racional del bosque. Así, se les impulsó a sobrevivir de la única forma posible: Incendiando y cultivando trigo sobre las cenizas (OTERO, Luís. 2006. La Huella del Fuego. 112pp.)